The Ruins of Corregidor

January 22, 2013

I would guess that when people think of ruins in the jungle they usually think of something in Thailand, Cambodia, or Mexico. Some great ruins there, but for something a little different, consider these…

All these pictures are of Corregidor Island and posted with permission from Steve and Marcia on the Rock. Check out their blog for a treasure trove of photos and stories from Corregidor.

Corregidor Island is the most well-preserved World War 2 battlefield. The remaining structures have a familiar look, but an otherworldly feel to them. One of the most bombarded 3 square miles in the world, it hardly had any vegetation left after the war. But you can’t keep a good jungle down.

The ruins of Corregidor have been repeatedly used as a movie set (for better or worse), either as themselves, a battle stage in a Vietnam war movie, a gang hideout in a post-apocalypse flick, etc. This post is a reference list of movies that feature the ruins of Corregidor. More will be added as I find them. Let me know if you come across a filmed-on-Corregidor movie not on this list (not including stock footage).

The “Cirio H. Santiago” category. Cirio seems to have been the most prolific director on Corregidor. First is one of his Post-Apocalypse movies, then a bunch of Vietnam War entries…

Wheels of Fire (1985)

Corregidor ruins show up for about five minutes as a post-apocalypse militant gang hideout. Also of note is the painting of additional ravaged ruins into the scene during an outdoors shot of one of the batteries (perhaps Wheeler). Makes it look extra epic. Cirio recycled the same painted ruins scene for a few seconds in Raiders of the Sun (1992).

Eye of the Eagle (1987)

Corregidor is the headquarters of a “lost command”. Lotsa shots of the ruins and Battery Way throughout the movie, culminating in an explosive finale. A couple pictures in my Guide to Cirio’s Nam Movies show Corregidor ruins.

The Expendables (1988)

Terminate shirtless Vic Diaz and rescue the kidnapped nurses from the ruins in Cambodia!

Nam Angels (1989)

This contains the infamous gasoline torture scene involving the unfortunate South Vietnamese capitalists tied to the big guns at the abandoned fortress.

Field of Fire (1991)

In the other Nam movies it’s the “bad guys” that control the Corregidor ruins. This time it’s the US soldiers that defend the “Fort Bien Hoa” ruins.

Kill Zone (1993)

Corregidor as weapons depot. Brief exterior shot and some interior shots that may actually be from Intramuros, Manila.

The “Corregidor as Corregidor” category…

Impasse (1969)

This movie has a common theme: find the gold hidden in post-war Philippines. The gold is on Corregidor, of course, so the final 35 mins or so is among and under the ruins. Notable for starring Burt Reynolds AND Vic Diaz.

Fortress of the Dead (1965)

A moody ghost tale by Ferde Grofe Jr. set on Corregidor Island with great B&W shots of the ruins and tunnels. Warning: this contains a totally unexpected and eye-popping wet t-shirt scene about mid-way through the movie.

The ‘I haven’t seen these yet” category…

The Hell Raiders (1988)

Another one by Ferde Grofe Jr. I haven’t watched this or ever seen it available anywhere, but the Dutch VHS cover clearly shows scenes filmed on Corregidor, as seen at When the Vietnam War Raged…in the Philippines.

Island of the Living Dead (2006)

One of Bruno Mattei’s final movies and it looks like a hoot. Looks like I need to rewatch some of the earlier Mattei movies to see if he ever used Corregidor previously.

Beware the “Black moor hens”!

December 29, 2012

It’s been awhile, months at least, since I’ve read a good passage of jungle description. Page 134 of Guerrilla Padre in Mindanao by Edward Haggerty, in the Cotabato jungle…

“But such a forest is beautiful only from the outside. A narrow trail winds through mud and creek beds in a gloom that weighs one down with its heaviness. You see no birds of gorgeous plumage, no woodland flowers blooming in the grass. Leeches cling to your ankles and insidiously crawl up your legs. They suck the blood from your neck and from behind your ears and leave infection that spreads to a horrible tropical ulcer. Inch-long needles of rattan pierce your feet and hands and face, thorns rip your clothing and pierce to the bare shoulder. A vine may cause an itch; to save yourself from slipping, you grasp and innocent-looking branch and your hand is pierced with a hundred small punctures which leave a sliver inside which swells and festers. There is no water in the slimy brook to drink, and troops of insolent monkeys chatter angrily as you pass, and the weary feet that strike an innocent-looking bit of rattan may launch a sharp bamboo spring into your legs–traps set for pigs and deer and human enemies. At night mosquitoes bite with the deadly sting of malignant malaria which kills after the first symptoms in three or four days. These and more, much more, is a tropical forest, even a forest with a good trail.”

A few pages later (141-142) they enter a swamp…

“Once we had entered the lake at the marsh’s center, we paddled at fair speed across it for hours. At times huge floating islands, blown by the wind, caused detours; again our paddlers took to their forked poles to push us through floating grass. Gigantic water lilies with leaves ten feet across, made a great green cushion, acres in extent, with flowers of embroidered pink. Black moor hens, or mud hens, with pink beaks and feet, ran over the leaves or dived suddenly into the water. Fishermen with three-pronged forks speared into the mud when bubbles showed a fish. Wild ducks in squadrons of hundreds swept by at dusk. Huge cranes, their necks bulging with fish, rose heavily as our vinta passed. As we entered the Buluan River monkeys chattered in the trees and swung on vines above our heads. In vain we look for crocodiles, in this region once so filled with them. A few years before the war one datu alone filled a contract for five thousand skins which are now portfolios, pocketbooks and shoes.”

Escape From Davao and Never Say Die

November 3, 2011

One of the great things about having my mother-in-law stay at our house for a few weeks is that she does all the dishes each night. So I get more reading done than I usually do. Here’s a couple that I was able to scratch off my “to read” list.

Escape From Davao (John D. Lukacs, 2010). Most Americans are aware of the Bataan Death March in 1942. A few may know of the Cabanatuan prison raid in 1945. Even fewer have heard of the escape of ten Americans and two Filipinos from the Japanese prison camp at the Davao Penal Colony in 1943. This excellent book is the author’s attempt to reintroduce to the world the story of these daring men: Ed Dyess, Jack Hawkins, Austin Shofner, Mike Dobervich, Melvyn McCoy, Stephen Mellnik, Leo Boelens, Sam Grashio, Paul Marshall, Bob Spielman, Benigno De La Cruz, Victor Jumarong, and all the men and women who helped them along the way.

The work done by Lukacs in creating this book was extensive: interviews, travel, pages and pages of references, etc. Stories from a few of the escapees had been previously published elsewhere, but Lukacs ties all the accounts together and supplements them with his own research. The result is what will likely forever be the most important book about the only significant escape of American men from a Japanese prison camp during WW2.

Never Say Die (Colonel Jack Hawkins, USMC, 1961). This is one of the previously published accounts of the escape. A nice little book, but doesn’t contain much that isn’t found in Escape From Davao. Notable for its additional details about the Mindanao guerrillas and preparations for the arrival of the Narwhal at Nasipit Bay in November of 1943.

Colonel Hawkins is the last surviving member of the escapees, having recently turned 95.

It was cool to find an inscription in my copy of Never Say Die. And the bookseller's business card made me chuckle.

Where’s the jungle, you say? The Japanese were thinking “Jungle as Prison“, but the escapees were thinking “Never Say Die”. They made epic journeys through swamp and jungle after escaping from the prison camp. Here’s what Hawkins had to say about the wild interior of Mindanao:

The merciless swamp was cutting deeply into our reserves of physical endurance. Our feet sank far into the clinging mud beneath the thigh-deep water, and each step required a tiring struggle. The matted grass towered above our heads, engulfing us and holding us immobile, like flies in a spider’s web. The midday tropical heat was intense, turning the swamp into a vast steaming cauldron which wilted our vitality. Rest was impossible, for there was no dry place to sit down.

…

Soon we found ourselves beyond the realm of civilization in a pristine wilderness where time had stood still through countless centuries. Nowhere was there evidence of human life. Monkeys peered curiously down at us from lofty perches in the giant trees of the primeval rain forest and chattered in alarm as we passed. Brightly plumaged birds added brilliant flashes of color to the wild scene, and their shrill calls split the silence in angry protest at our invasion of their domain.

…

And then suddenly, as we rounded a bend in the stream, we found ourselves face to face with a band of Atas! We stopped short and stood motionless. They did the same. There were more than a dozen of them, not forty yards away. As we stood transfixed, they began ot advance along a gravel bar directly towards us. Thoughts of what to do flashed through our mind. Our bolos, I knew, would be of little use if they attacked with the long spears and bows and arrows they all carried. Should we run or stand our ground? It was too late to run.

…

The strange-looking party moved to within fifteen yards of us and halted, as yet making no menacing move. They stared at us and we stared at them, both sides in silence. Never before had I seen such people–short, bushy-haired men with copper-colored skin and heavy anthropoid features. Their upper lips protruded grotesquely from wads of betel nut underneath, and the blood-red juice trickled down the corners of their mouths, staining the skin. Except for scanty loincloths, they were naked. Each man carried an eight-foot spear and a bamboo bow with a quiver of arrows slung from the shoulder. They seemed spellbound at the sight of us, even as we were at the sight of them. Probably we were the first white men they had ever seen.

Then, as silently as they had come, they turned and padded away, disappearing in the dense foliage on the riverbank.

…

Soon we began to pass other Atas who came floating down the river on bamboo rafts–men, women and children. Like the first group we had seen, they all wore loincloths and seem addicted to the betel nut habit–even the small children. The narcotic effect of the betel nut possibly accounted for the strange, half-dazed look on their primitive faces. None of them approached us nor made any gesture of greeting.

…

Each Ata family lived in a tree-house, separated by a considerable distance from any neighbor. They never congregated in villages.

Is the Jungle Neutral?

June 14, 2011

The Jungle Is Neutral by F. Spencer Chapman, first published in 1948. The journal of a British officer conducting guerrilla operations in Malaya against the Japanese occupation. This work is often cited as a classic of jungle guerrilla warfare and survival.

Check out the wonderful journals and photos by Keong as he retraces part of Chapman’s path through the jungle. Keong’s site, My Rainforest Adventures, is a great collection of journals, photos, and tips by and for a modern-day jungle trekker. Lots of ways to start a fire in the jungle. Especially cool is the fire piston, a precursor to the diesel engine.

The myth of the jungle is that it is a wicked, inhospitable place. What does “the jungle is neutral” mean? It means the jungle does not care and is not a factor in determining if you live or die in the jungle. You are the deciding factor. Keep your head and your senses and your feet and the jungle will help you. Lose them and the jungle swallows you.

I Love Trash

June 7, 2011

Too Late The Hero (Robert Aldrich, 1970). If only they had cut at least 30 minutes from this flick, mostly from the boring first half, this could have been a classic WW2 movie. The Philippines jungle crawl in the second half is good stuff. Worth watching to see Boracay before it became overrun with tourists and high-rise hotels.

Code Name: Wild Geese (Antonio Margheriti, 1984). IMDB indicates Hong Kong and the Philippines as filming locations, so I’ll assume the jungle scenes were done in the Philippines. They are only okay, but the main reason to watch this flick is the final battle with Lee Van Cleef and Klaus Kinski. Brings a whole new meaning to the phrase “fire in the jungle”.

Strike Commando (1987). Directed by Bruno Mattei in the Philippines. When it comes to low-grade Vietnam War/Cold War movies, it’s hard to get more low-grade than this. Therefore, we can laugh as we watch it and appreciate its existence as a cultural artifact. Namedropping this flick can earn you serious cred with “bad movie buff” folks. Regarding the jungle stuff, some good stuff and some “not jungle” coconut plantation stuff.

Behind Enemy Lines (1986). Directed by Gideon Amir in the Philippines. Not to be confused with several other movies of the same name, this one is also known as P.O.W. The Escape or Attack Force ‘Nam and stars David Carradine. He plays a serious, dedicated colonel and doesn’t crack a smile the entire time, but I got some good laughs watching this flick. Maybe the Tanduay 1854 had something to do with it. Jungle footage is decent, though much of it looks like a coconut plantation to me. Bonus points for the punji rack trap swinging down from the trees.

They Fought Alone in the Jungle

May 25, 2011

The Japanese were twenty miles away. If he moved, he would starve. If he stayed where he was, he would be killed.

There was an alternative. He could chuck the whole bloody business.

Since Bowler was presently unable to take over the net, Fertig could surrender control of the guerrilla to Supreme Headquarters, cache his radios, and tell his men to scatter into the hills. A few men, traveling alone, could always find something to eat. He could wander across the mountains, searching for food, until The Aid came.

Why not? Hadn’t he done enough? After the Regular Army surrendered, his makeshift army had killed seven thousand Japanese. He had re-established a government. He had denied the Japanese any practical benefit of their conquest of Mindanao. Instead, Mindanao had been a constant drain on Japanese resource. They had had to divert 150,000 men to Mindanao in an unsuccessful effort to crush resistance. From an arithmetical standpoint, it was already an enormous victory. Forty thousand guerrilleros had killed seven thousand of the enemy and, in effect, taken 150,000 prisoners. There was also the incalculable benefits accruing from guerrilla intelligence. Supreme Headquarters had never specified whether any particular sightings had led to any particular sinkings, but the Navy had sent the coastwatchers its highest compliment: Well Done. More important, the guerrilla had done much to restore the face America had lost by its abject surrender. The Filipinos would never again allow Americans to call them “little brown brothers.” After all, the resistance was almost entirely a Filipino operation: Fertig was an invited guest. But Americans who refused to surrender, and instead accepted the invitation, had done much to salvage the essential image of an America that was the friend of the Filipino people.

(…)

Fertig felt the wight of the Moro silversmith’s stars on his collar. He was Colonel Fertig to (the American headquarters in) Australia, but here on the island he wore his stars. On Mindanao, he was, and would remain, The General.

—

The above is excerpted from They Fought Alone by John Keats, recounting the thoughts of Wendell Fertig as his guerrilla headquarters deep in the jungle interior of Mindanao was hemmed in by the Japanese and running low on supplies. A previous post this week also excerpted this book. The comment about “A few men, traveling alone, could always find something to eat” reminded me of another recent post here about food shortages in the jungle.

The Filipino guerrilla movement against the Japanese occupation is a relatively little-discussed aspect of WW2, but this is one of the more well-known books about it and there has been rumors of a possible Brad Pitt movie based on it (all movies trying to secure funding will star Brad Pitt, don’t ya know?). They Fought Alone was first published in 1963, coincidentally, just as the Vietnam War was about to escalate. It demonstrates that the US had plenty of experience as jungle guerrillas in Southeast Asia, with knowledge of how they succeed and how they could be defeated. It’s a shame that US leadership during the Vietnam War seemed to ignore some of the lessons in this book.

Though They Fought Alone is heavily based on the journals of Wendell Fertig, it must be noted that it’s actually a novel and therefore should not be depended upon for historical accuracy. Clyde Childress, an officer under Fertig on Mindanao, wrote a rebuttal and critique of the inaccurate history and self-serving nature of They Fought Alone. Download a PDF of the rebuttal here. At times, Childress seems to paint Fertig as a real-life Kurtz character: an aloof leader commanding a force deep in the jungle! (Remember…Apocalypse Now! was filmed in the Philippines.) Unsound methods? I wouldn’t go that far, but Childress ends his rebuttal with this:

“What baffles me is how this man, with such an overweening desire to create a distinguished reputation for himself as the great guerrilla leader, could allow these personally damaging remarks that expose his obviously unsound frame of mind to creep into his biography for everyone to read and assess. This is indeed a strange book!”

Whatever the case may be, Fertig was successful at what he set out to do on Mindanao. The Filipino guerrilla movement was fractured and disorganized in many parts of the Philippines, as shown by the map below. The physical isolation of the many islands explains some of the disorganization, as does the concentration of Japanese forces in some areas. For Fertig to unite the freedom fighters of Mindanao under his command was an accomplishment, considering how the island was and still is embroiled in bloody conflict between numerous religious and political divisions.

…and a band burst in to “Aloha.”

May 23, 2011

The following is excerpted from They Fought Alone by John Keats, describing the mid-November 1943 arrival of the submarine Narwhal to Nasipit Bay, Mindanao, in Japanese-occupied Philippines, approximately one thousand sea miles behind enemy lines:

The words South Sea Islands filled Evans with an almost unbearable delight, and he thrilled, too, to phrases like war zone, clangor of arms, and savage enemy. To Evans, a jungle was always a forbidding jungle, invariably to be found covering mysterious hills. He therefore peered with tense joy at the scene in the periscope–the scene he had come ten thousand miles to see, and which now promised to fulfill his dreams exactly. In fact, he had dreamed of it so long that it looked familiar: the blue mountains rising out of the sea; the dense vegetation growing to the waterline; the coconut palms standing sentinel along the narrow beach; the clouds forming out of the rain forests on the flanks of volcanic hills. He was looking at his own South Sea Island, populated by an enemy savage enough to satisfy any adventurer’s demands, and soon he was to live the drama of a guerrilla soldier in a tropical paradise. Regretfully, he surrendered the periscope to Captain Latta, who had allowed him this one brief view. Evans resigned himself once more to the pale world of oil-smelling machinery stale air, and dim yellow light that was the Narwhal‘s belly. The submarine’s tanks filled, and she settled to the sea floor to await the dusk.

(…)

There were dockworkers to grab the Narwhal‘s flung messenger lines and haul the heavy Manila cables over bollards; seven trucks waited on the dock apron; launches with lighter barges waited in the river; excited Filipinos laughed and waved to the men on the Narwhal; girls in filmy dresses waved and then covered their faces with their hands to conceal the embarrassment they were expected to feel for having been so forward, and a band burst in to “Aloha.”

The band, all dressed in white trousers and white shirts, was the military band of the 110th Division of the United States Force in the Philippines, Colonel McClish commanding, and as the Narwhal‘s lines were secured, the bittersweet languor of “Aloha” filled the tropical night and in the light of moon and flickering torches, Evans could see tears streaming down faces brown and white and he heard one of the Narwhal‘s sailors shout huskily, “Jesus Christ, where the hell are we? Hollywood?”

The Narwhal‘s cargo hatches opened, and the band blared “The Stars and Stripes Forever” with a fervor probably never matched before or since, and sailors in blue denim and bare-chested brown men in shorts worked together to unload the huge submarine. Supplies poured out of her: cases of carbine and rifle ammunition; cases of submachine guns, carbines, rocket launchers called bazookas, D-ration chocolate bars, Spam, cheese, magazines, books, MacArthur’s newspaper the Free Philippines, medicines, jungle boots, suntan uniforms, jungle camouflage suits, .50-calibre machine guns on tripod mounts, 20-millimeter cannons, millions of pesos in counterfeit Japanese invasion currency, cases of atabrine pills, the new anti-malarial. There were printing plates and paper for the manufacture of legal guerrilla currency, jungle hammocks, cigarettes, flashlights, officers’ insignia, and spare parts for generators and radios; tools and spark plugs. All this, and more, came pouring out of the Narwhal as the band played songs that had been popular in 1941, which were the most recent songs the bandsmen had heard, and one of the sailors called out to the dock, “Hey, where are the Japs?”

“What’s the matter? You getting nervous in the service?” a voice answered in good American, and Evans saw a thin, grinning figure in faded, patched khakis push through the dockside crowd.

“It’s no sweat,” the guerrillero told the sailor. “The Japs are a mile away.”

“Mile away? Which way?”

“Oh, a mile that way,” the guerrillero said, gesturing. “And a mile or maybe two miles over that way.”

“Jesus!” the sailor said, and the people on the dock laughed.

Evans looked at the guerrillero and wondered how long it would be before he, too, had long hair and a straw hat and a uniform as ragged; before his skin, too, was sun-bronzed and he went about barefoot with a gun on his hip and a rifle slung over his shoulder and was nonchalant about the Japanese being a mile away.

“How long you been here?” the sailor asked, and Evans heard, as though in a dream, the guerrillero say, “What do you think we do? Go home for week ends? We been here since it started. Where have you guys been?”

No Farewell to the Dead Heroes’ King

March 17, 2011

Here’s two jungle movies that don’t really have anything in common, except that they would have been improved by the presence of Bill Murray.

Farewell to the King (1989). Theoretically I should have loved this movie. WWII jungle with natives and guerrillas. Directed by John Milius, who was involved in some of my favorite movies: Conan the Barbarian, Apocalypse Now, Jeremiah Johnson, etc. The Malaysian jungle is lush and wonderful but Nick Nolte was miscast and ruins it all. I would have preferred to see Bill Murray in the role instead.

No Dead Heroes (1986). Directed in the Philippines by Junn Cabreira. Insane story of a Vietnam POW that was taken to Russia and implanted with a chip in the brain to make him the ultimate assassin. The chip is remote-controlled by a wristwatch, of course. Great jungle footage with elaborate bamboo prison camp and ancient stone ruins sets. Mike Monty is in many of these trashy ‘Nam flicks and always plays the same serious officer character seen doing a mission briefing at the beginning of the movie and always gives the same performance as if he were reading his lines for the first time off of the cue cards. Awkward pauses, monotone delivery, and misplaced emphases. I would have preferred to see Bill Murray in the role instead.

The Obsession of Men in the Jungle

February 9, 2011

Here are four movies in the Fire in the Jungle Hall of Fame:

Oro, Plata, Mata (1982) directed in the Philippines by Peque Gallaga. The jungle scenery is beautiful, especially the waterfalls. This is considered by some to be the greatest Filipino film of all time. It is quite an eclectic movie, with some elements similar to The Godfather and Gone With the Wind, some balls-out action and gore scenes, and even some Filipino mythological fantasy. It is the best movie I’ve seen about the Filipino guerrilla movement during WW2…until that Wendell Fertig movie gets made, at least.

Aguirre, The Wrath of God (1972), directed in Peru by Werner Herzog. One of the earliest color films to present a lush, harsh jungle, establishing Herzog as a master of the technique. Whenever I watch this movie it seems too short and I am disappointed when it ends because I want to see more of the story and the setting. Many memorable scenes in this movie, but one that I often think of is when the expedition slowly trudged its way through the muddy jungle in their heavy armor, cargadores hauling all their extraneous equipment.

During some playtesting for the upcoming Fire in the Jungle fantasy RPG supplement, my friend wrote this great description of his party of adventurers pushing through the sloppy jungle, just like Aguirre and his conquistadores:

The sickly cleric demands his acolyte help him onto the top of the supplies and refuses to walk. He holds a parasol to protect him from the sun, even though the light that reaches them is already filtered by the dense overgrowth. The cute magic-user swelters in her elaborately embroidered and too-thick robes that continually get caught in the undergrowth; she makes her apprentice carry the heavy spellbook strapped to her back with various tinctures and components and all the writing supplies in a front-pack strapped to her chest. The fighting man grimly struggles to lead the mules and cut a path with his ‘squire’, really a cousin his mother made him bring, pushing the cart from behind. The squire is covered in mud, mule shit, undergrowth, and sweat. The thief and elf take “rear guard” but mostly just make noise with their ribald jokes and too-loud and forced laughter.

The next two both feature a river journey through the jungle, somewhat mad and obsessed characters, and had documentaries about the films’ creation and their somewhat mad and obsessed directors.

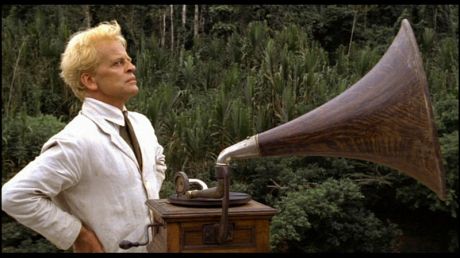

Fitzcarraldo (1982). Directed in Brazil and Peru by Werner Herzog. The third film on this blog directed by the jungle master (Aguirre Wrath of God, Rescue Dawn). The idea of dragging a boat over a jungle mountain and how it was accomplished in this movie is fascinating to me. All in the hopes of building an opera in the jungle! Burden of Dreams is the documentary about the creation of Fitzcarraldo and is just as good as the full movie.

Klaus Kinski as Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, the man who will bring the voice of Enrico Caruso to the jungle.

Apocalypse Now (1979). Directed in the Philippines by Francis Ford Coppola. Not much I can say about this movie that hasn’t been said elsewhere. The jungle scenes just prior to the tiger’s appearance is a wonderful depiction of deep, dark, thick canopied jungle. The documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse is an interesting look at the struggles and disasters that hampered the creation of Apocalypse Now.

Loboc River, Bohol, Philippines, 2009. While on this river boat, my wife says "It's like that movie you watched." You see, she hasn't seen Apocalypse Now, only watched me watching it.

Finally, the novella Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad must be mentioned here. First published in whole form in 1902, its influence on these two films is well known. It is in the public domain so the text and several free audio recordings are available for free download all over the internet.

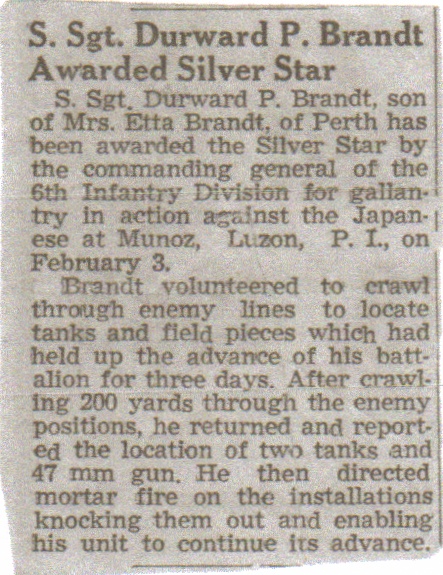

Grandpa in the Jungle

February 3, 2011

66 years ago today, my grandfather did something special in the Philippines:

Sadly, he died shortly before I was born. He didn’t talk much about the war to family, so I don’t have any war stories to tell here. He did feel the effects of malaria for the rest of his life.

The Battle of Munoz was against perhaps the largest concentration of Japanese tanks encountered during the war. A report and study of the battle can be found here.